Criticisms

A Protest against Silent Inaction

2011.08.20

Lee Jinmyung | Curator

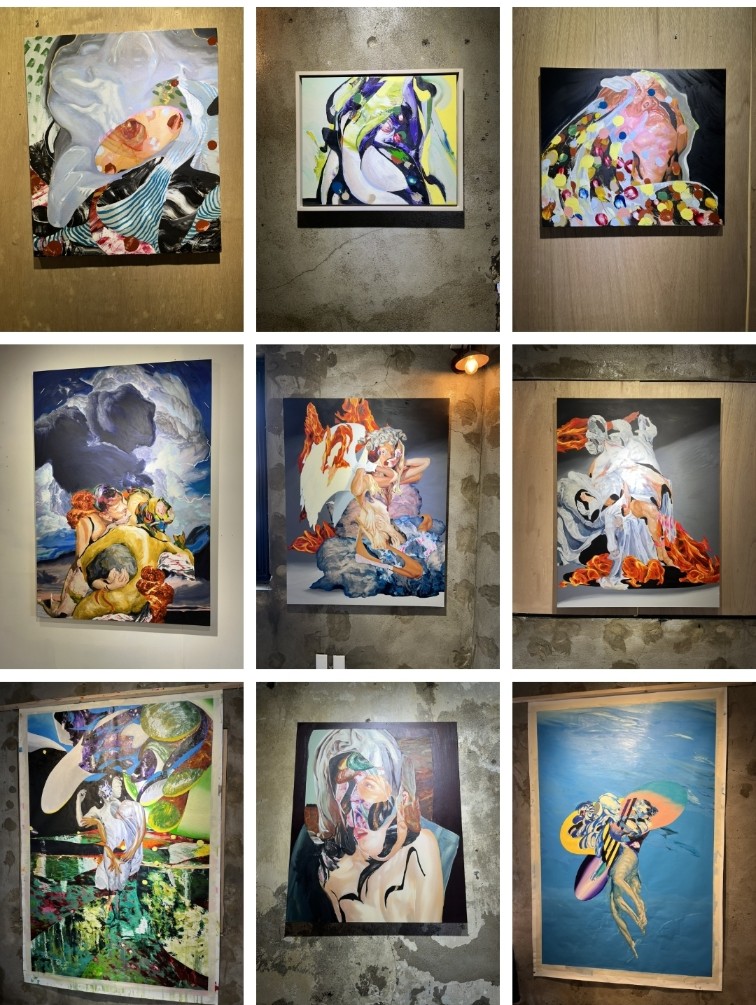

Park's Park 9, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 133.3 x 193.9 cm ©Park Jung Hyuk

‘Only he is alive who rejects his convictions of yesterday.’ (Kazimir Malevich)

‘Pornography is a form of the spirit’s battle against the flesh, a form that is thereby determined by atheism, because if there is no God who create the flesh, then there are no longer those excesses of language residing in the spirit that aim to reduce the excesses of the flesh to silence.’ (Pierre Klossowski)[1]

Ⅰ.

Martin Niemöller, a theologian and Lutheran pastor during World War II, was initially a conservative and rather passive observer of the Nazis. What finally broke his silence and caused him to protest against Hitler was the Nazi persecution of the Christian Church. Niemöller later confessed his deep regrets about not speaking up and thus allowing countless victims to perish in the hands of the Nazis.

They came first for the Communists, and I did not speak up because I wasn't a Communist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak up because I wasn't a Jew.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak up because I wasn't a trade unionist. Then they came for the Catholics, and I did not speak up because I was a Protestant. Then they came for me, and by that time no one was left to speak up.[2]

The Nazi brutality is just one of many types of dominant social conditions that we have seen in human history. My purpose here is not to discuss the evil deeds of the Nazis. Rather I wish to point out that the world is constantly evolving regardless of the right and the wrong, or the good and the evil that may go on. Various forces, or social conditions, underlie the ostensible occurrences in the world. And the world shifts even if the individual does nothing. In fact, the not doing actually contributes to the movement of the world to a certain direction, which in political science is often referred to as silent inaction. Silent inaction is very common in reality, and yet it is unseen and therefore the more terrifying servant of the dominant social condition.

If there is one area in the real world where this silent inaction is fundamentally rejected, it would be none other than Art. I make this claim because Art is a lifelong project in which the artist protests against the existing visual principles and the clandestine workings of the established art world to propose and to have evaluated new visual principles of one’s own making. Therefore, the artist must study the long history of artworks while also understanding the nature and habits of the dominant social conditions, a monster live and evolving. At the same time, the artist must bring to life an aesthetic mechanism to project his thoughts and feelings onto the thoughts and feelings of the viewer.

For the artist, everything is a viable theme: history, politics, economy, society, ecology, community, universe, gender, race, future and on goes the list. An artist who prefers to passively follow the established system and form does not deserve to be associated with critical resistance or admired as a visual thinker, though he may enjoy the fruits of conservative commercialism to a certain extent.

The long discussion thus far was meant to set a context for understanding the artistic trajectory of Park Jung Hyuk. The first target of Park’s resistance, in fact, is the silent inaction of the masses. Their submissive bias, he points out, often breeds an unquestioning acceptance of the designs of the ruling, which in turn spawns vain desires that consolidate a unilateral relationship between the ruling and the ruled. According to Park, desire is the comic bait that is the real power subjugating the absolute majority.

The first time this progressive artist made a name for himself was in 2004 Gwangju Biennale where he staged the "KMDC project". Park organized a stray dog contest in which decrepit, old and plain canines were awarded prizes based on the number of votes each garnered from Biennale visitors. The relationship between the stray dogs and the contest is analogous to that between the artist and biennales, and between the politician and elections but not limited to these. The use of such satire to overturn blind indulgences led Park to experiment with other forms of art, often in ways he himself could not have anticipated.

One such example is 166cm, a video installation made in 2004 soon after Park entered his thirties, which is arguably one of his most remarkable expressions of the existential being. It is a record of his grandmother’s last battle against the great equalizer. Her shrill cry in the throes of death tells us that Park’s satire in all his works is more than just play and that it is full of real pain and suffering. In this piece, the dying grandmother represents the one absolute value that defies objectification, family. Yet, Park pushed himself to objectify the emotions that raced passed him as a life once full of joy, rage, love and its ups and downs lay dying before his eyes, so that he may overturn that fixed infatuation with family. He had thus declared a war against biases and dichotomous thinking.

Ⅱ.

There is an unforgettable line in the play Peer Gynt by the renowned Norwegian writer Henrik Johan Ibsen. It goes: “Best be howling with the wolves that are about you.” Park Jung Hyuk does not heed this advice. When the wolves howl, Park would much rather point the gun or throw a rock at them rather than join the chorus, the wolves being in this case artistic conventions. To better understand Park’s endeavors as such, one must also understand an unanticipated and little known consequence of the de facto fall of socialism in 1989. The collapse brought about a collapse of something else, namely the wall that had divided the elitist art and the people’s art, or minjung art as it is known in Korea.

These two contending groups had fiercely opposed each other until their joint demise triggered by the end of socialism and gave way to a flood of Western influences. The French post-structuralism was embraced in an effort to find an alternative to the bygone Marxism, and Western forms and styles were uncritically adopted as a growing number of artists and scholars educated overseas entered the Korean art scene. The triumph of Western liberalism over East European socialism lured progressive intellectuals and critical artists to pursue profit over beliefs and to compromise with the system rather than search for true meaning in life.

Obsession, nervousness, decadence, dandyism, fashionism and exoticism pervaded. Images from TV, cinema, videos, cartoons, Internet and imported books inundated the Korean cultural sphere to unprecedented levels, while the society for the first time faced illicit image sharing at a massive scale as a result of weakened censorship. It was amidst this confusion that Park developed his artistic spirit.

Park’s peers in the 1990s almost competitively raced West. Various media were embraced without question, and artworks that were little more than copies of the Western art proliferated. These imitations of dubious authenticity were introduced by artists educated abroad and graced the walls of art museums. Notable is the Whitney Biennial in Seoul in 1994, which was promoted as a rare opportunity to experience the essence of postmodernism. The exhibition showcased commercially successful artists such as Robert Longo, David Salle, Eric Fischl and Julian Schnabel, who have branded themselves and their art on top of their unique methodologies and styles.

Park suffered under the pressure and lure of commercialism that was foreign to him but now claimed to be the mainstream. He was also torn between the newly emerging artists who espoused media-centrism and a slightly earlier generation of proponents of the defunct people’s art. Ultimately, he sought his way out by returning to the very base of it all. He asked himself what justified Art in the face of the world and what historical inevitability explained the continued existence of Art.

Although Park has not fully answered these questions as yet, no one can deny the earnestness of his pursuit. He has sojourned through the world that pains him, a world full of silent inaction and acquiescence. He suffered from watching the blind leading the blind as in Pieter Bruegel’s painting and those who follow whoever is leading as sheep are prone to do even to the extent that an entire flock would jump off the cliff after the presumed leader. Park critiques that the human being almost always relies on the methods of conceptualization and categorization in order to make sense of the world and necessarily accepts biased assignment of value. The human being, in other words, understands A by misrepresenting B.

Take for example malocclusion, a frequently found motif in Park’s paintings. Malocclusion is a term that refers to the misalignment of teeth of the upper and lower jaws. While it is a condition that has always existed, it became widely known in Korea only in the 21st century thanks to ingenious marketing by dentists. Now, our common sense knowledge dictates that those with protruding upper jaw are abnormal and suffering from malocclusion and only those whose upper and lower teeth meet nicely in a line are normal. However, no one in the world has the right to categorize people into the normal and the abnormal based on the malocclusion criterion.

Another concept which Park highlighted in his works is resupination, which simply means that a plant’s organs are in an inverted position. Resupination does not, in and of itself, hinder the growth of the plant or in any way obstruct its flowers from blooming. It is simply a botanical concept. By looking into these essentially neutral concepts which have often been used from a biased perspective, Park sought to uncover the violence inherent in conceptualization and prejudiced judgment. This is precisely what he believes is the artist’s responsibility at its bare minimum. Though it may seem only a small action, it is nevertheless what distinguishes Park from the other artists who resign themselves to silent inaction.

Martin Niemöller, the aforementioned theologian, repented his past inaction and became an anti-war activist. He said that he gained two valuable principles while suffering the tragic consequences of his silence: “obsta principiis”, meaning “resist the first encroachments” and “finem respice” which means “look to the end”. As an artist, Park has practiced these two principles quite well. He cast rocks at the pack of wolves in his resistance against the institutionalized art. Though this isolated him, he found reassurance in the fact that he had done something.

This confidence then led him to ‘look to the end’, which he realized in 2008 was to become a painter whose works speak for an entire generation. To walk towards that end, he felt he had to let the world understand the futility and the fear paralyzing his generation. Consider for a moment the modern history of Korea, and the first generation to truly internalize commercial capitalism was born in the 1970s, and Park happens to be one of them. This internalization was achieved not by brainwashing or repetition of rhetoric. It was an overflow of images, fast-moving, provocative and donning the shade of civilization that swamped people and bred in them the seeds of commercial capitalism. It was also this that compelled Park to produce a series of paintings on the deep sense of futility and fear shared by his generation.

Images of pornography, religious iconography, the violence inherent in the malocclusion concept, commercial products, sexually-charged corporal punishment, animalistic vigor, burning flames, and in sum total decadence pervade his paintings. There is neither center nor periphery. There is neither hero nor his sidekick. Just as dinosaurs became extinct as a result of the unsustainable consumption they required, and just as the moai sculptors of Easter Island met their tragic end, catastrophes come without any distinction of the left and the right, the high and the low. The images bursting forth from Park’s canvas represent the advance guards of the consumption mechanism which will usher in the catastrophe capable of bringing the entire human race to an end.

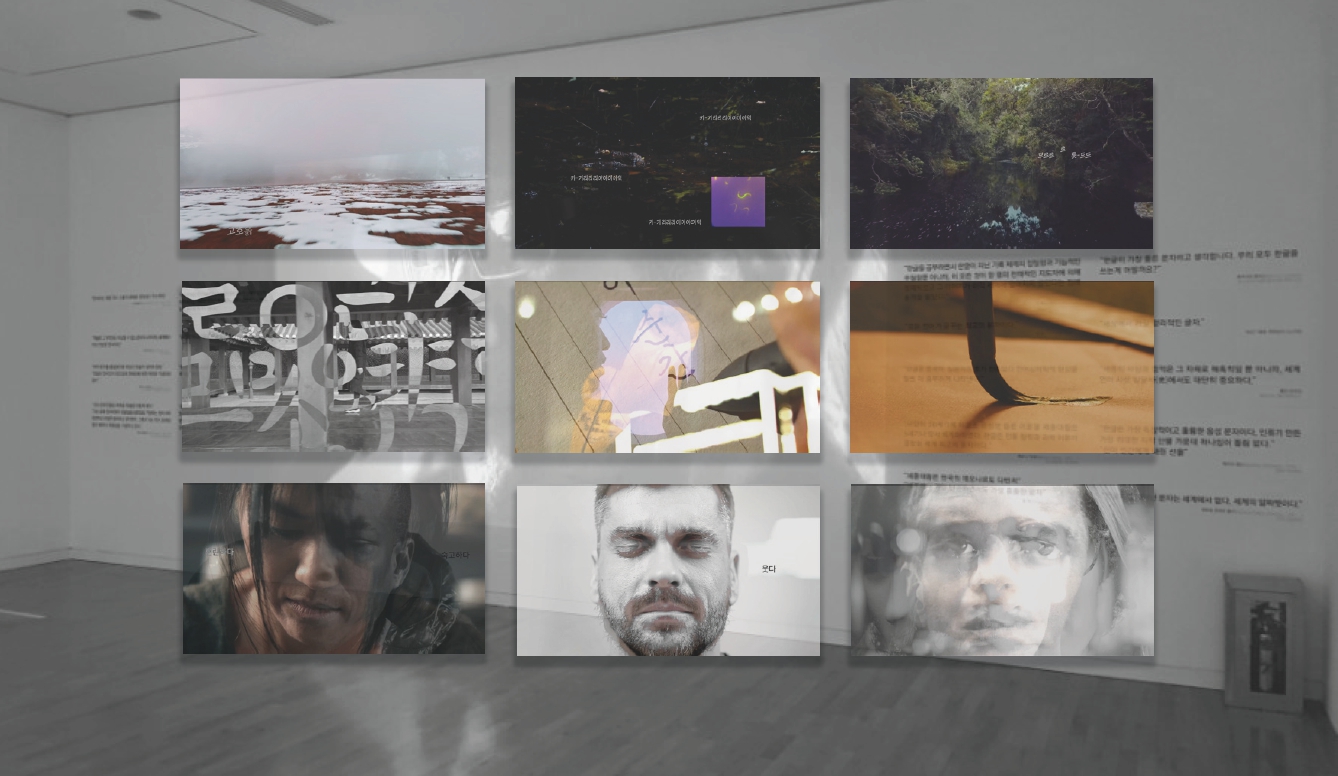

The meaning of Park’s works and furthermore the purpose of Art are epitomized in his latest video art piece titled ‘Ordinary People’. The installation consists of five videos played simultaneously. The videos were created by dramatically piecing together scenes from some 50 films and soap operas from across the world. Using a found footage approach, Park captured the wide spectrum of human emotions. Each video has a climax that highlights these emotions: a person screaming out in anger, random and uncontrolled firing of the gun, and a dog howling in distress.

Whenever one of the five videos reaches its climax, the other four screens surrender and serve as mise-en-scène for the dominant one. This, explains Park, is analogous to most cinema and TV productions which are structured with a dramatic climax on top and all other elements existing only to serve that moment. Whether it is the primal scream, the random gunfire, or the unstoppable tears, the expression of emotions is something we cannot and must not obstruct. As human beings we all share these emotion archetypes and need to let them out to the extent that doing so does not harm others.

However, our society has continuously evolved from first requiring us to moderate our desires, then to restraining and controlling them at will, and now it distorts and manipulates them to be abused for commercial ends. It is in this context that Park’s paintings need to be interpreted. There is a message and an intention in the decidedly plastic and fast-paced brushwork with which he rendered a seemingly random composition lacking both the center and the periphery. We must understand for he has put so much at stake to say that when we finally reach that critical point, it will be time for some serious atonement.

[1] Pierre Klossowski, Such a Deathly Desire, Sunny, 2007. P. 67.

[2] Milton Mayer, They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933-45, University of Chicago Press, 1966. Op. cit., pp. 168~169