Criticisms

Between the Fascination of Metamorphosis and the Drift of Imagery

2025.05.20

Lee Moonjung | Art Critic, Director of Leepoetique

A single phrase, like a single photogram, must be capable of delivering a rich range of visual stimuli within an unceasing flow of motion. (…) Every verb on every page appears in the present tense, as if all events were unfolding right before our eyes. New incidents rush in, and all distance between one and the next collapses into immediacy.¹

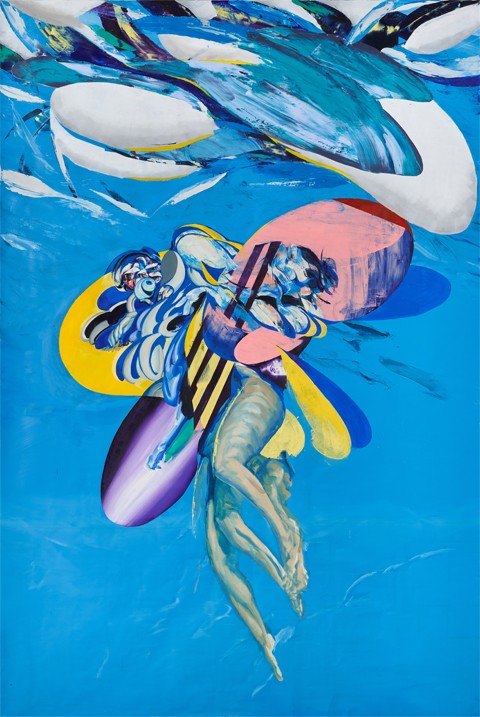

Forms whose boundaries are unclear—whether merging into one or splitting into several—fill the field of vision. A world composed of fragments that seem to melt, overflow, and escape any stable judgment unfolds before us. Despite the physical stillness of painting, the images writhe with movement.

What animates them feels less like liveliness than a kind of struggle. Every situation in the work is in the midst of becoming. Even areas filled only with color hold the viewer breathless with tension. These paintings resemble a visualization of an interior—mind, sensation, emotion, and thought pushed into a state of excess.

They feel like labyrinths carved from multiple depths, persuasive enough to be read as dreams or unconscious states of a fragmented, dispersed subject. They may also be the visualization of unresolved desire or memories that have been muddled together.

Although many of the images appear vaguely familiar, ‘Park’s Land’ (2021–) emanates an uncanny and peculiar atmosphere. This intensifies a tendency already present in ‘Park’s Park’ (2005–2014), where the artist quoted images he had collected but always subjected them to processes of external and internal transformation. In ‘Park’s Land’, fragments from artworks based on Greek mythology and biblical narratives appear frequently.

Even in the ‘Park’s Memory’ series (2017–2021)—oil-painted forms on silver PET film—classical mythological works such as Peter Paul Rubens’ The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (c. 1618) were referenced. Yet in ‘Park’s Land’, this component grows more substantial, and the motif initiated through Ovid’s 『Metamorphoses』 (AD 8) branches out in multiple directions.

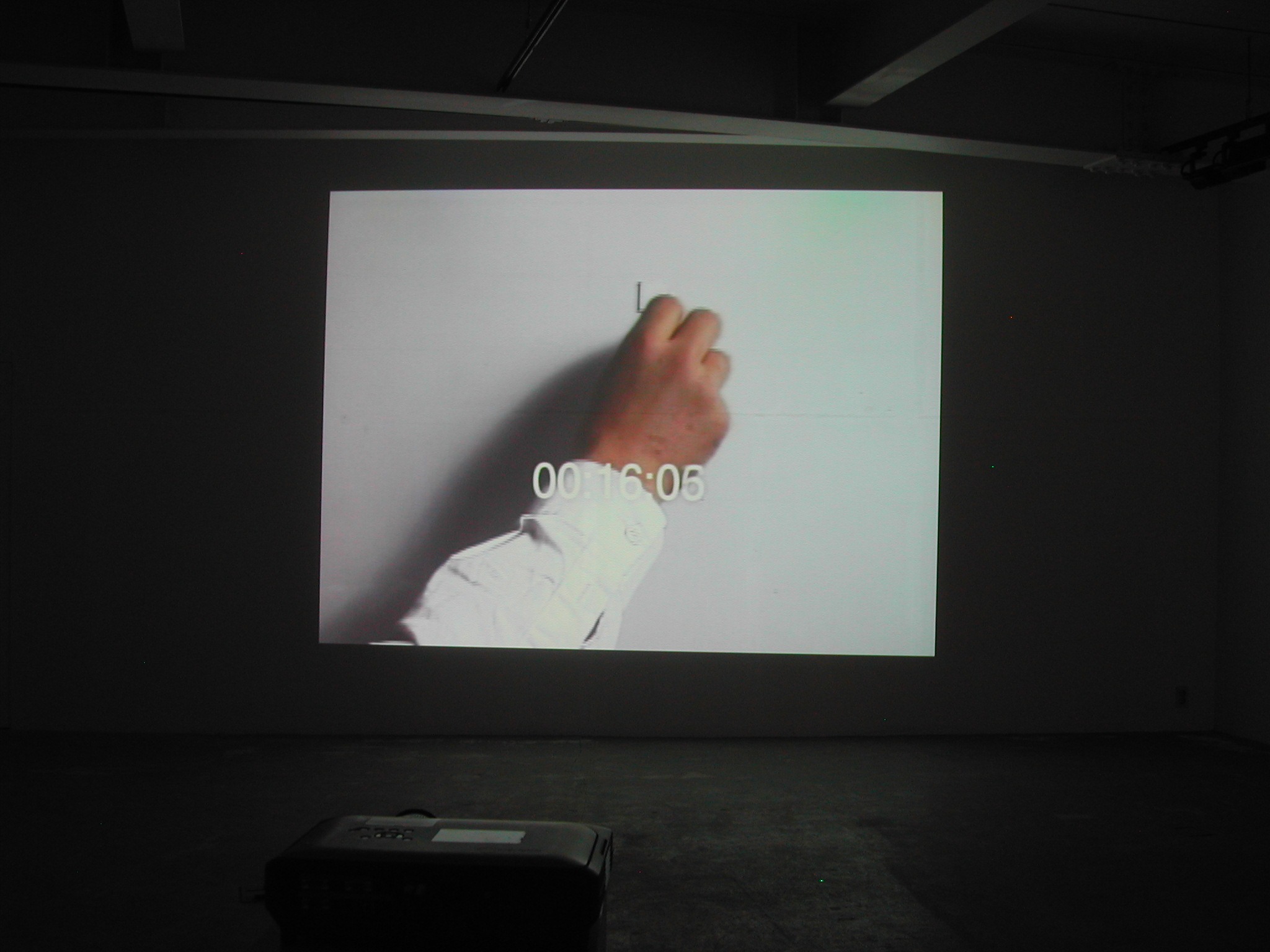

Installation view of 《Rebellious possibility》 ©Leepoetique

『Metamorphoses』 is a compendium of myths centered on transformation, spanning from the creation of the cosmos and humankind to the age of Augustus. Except for the theme of metamorphosis itself, it has neither a consistent protagonist nor a unified plot, thereby departing from the established traditions of epic poetry. Although it recounts the history of the world’s emergence, it articulates neither a definitive purpose nor a legitimizing narrative, which has led some to note its “skeptical and nihilistic undertones.”2

These characteristics would naturally have appealed to Park Jung Hyuk, who has long posed critical questions to fixed ideas and uniform modes of thought while simultaneously reflecting on inherited traditions.

Building on this foundation, the artist’s interests widened beyond the transformations that appear in Greek mythology to include the Incarnation and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, along with the mental and physical changes shaped by religious and philosophical convictions, systems of belief, and ideological forces.

It is for this reason that the most immediate keywords in ‘Park’s Land’ are undoubtedly transformation and myth. Transformation is conventionally understood as the alteration of one’s original form—whether voluntary or imposed—and is typically imagined as a physical change of the body or outward appearance. Even today, cultural and artistic narratives are filled with scenes in which humans become animals, plants, or objects; animals assume human form; or supernatural beings disguise themselves as mortals. Yet metamorphosis is not a rare incident reserved for mythic storytelling.

In reality, every human being undergoes a lifelong process of transformation simply by living—from infancy to old age, the body’s passage is more dramatic than most fictional events. People replace organs, surgically alter their features, or otherwise modify their bodies. As the artist himself notes, supplementary characters, alter egos, or avatars in virtual space also constitute further examples.3

Nor is transformation limited to the external body. Inner worlds—worldviews, emotions, thoughts, and beliefs—shift ceaselessly. Moreover, many people carry the desire to become someone other than who they presently are. They long not only for impossible, fantastical metamorphoses but also for changes in social or economic status, or to resemble a particular kind of person they admire. These desires arise from the pressures and constraints of reality and often reflect broader social demands. Imagining oneself transformed can relieve psychological dissatisfaction or conflict, offering a sense of liberation that invigorates daily life.

The desire for metamorphosis can thus serve as a source of energy rather than mere escapism or idle fantasy. It invites one to ask why such a transformation is desired in the first place and to reflect on the conditions that shape those aspirations. Ultimately, metamorphosis is grounded in lived experience.

Furthermore, because transformation traverses the boundary between the self and what is not the self, even fantastical metamorphoses can operate as resistant symbols—unsettling fixed categories and unbinding monolithic norms. Above all, art is inherently bound to metamorphosis. Something that exists only in the artist’s mind emerges into the world to become an object of viewing, interpretation, and critique. Through various material and conceptual processes, paint and canvas, clay and stone, metal, and even everyday objects are reborn as artworks.

Therefore, the metamorphic images in Park Jung Hyuk’s work should not be reduced to visual clues intended solely for iconographic interpretation. His canvases—where unfamiliarity collides with familiarity—become sites for exploring and generating critical meaning about the many kinds of transformations and changes endlessly attempted both within and beyond the human subject.

Park's Land 34, 2023, Oil on canvas, 130.3 x 193.9 cm ©Artist

On the other hand, myth is a body of origin stories that draw upon extraordinary and mysterious phenomena encompassing the world—narratives that describe the deeds of humans and heroes, the actions of gods, and the workings of nature. Because of this, myth is often assumed to carry a single, fixed meaning. Yet myth is not the creation of a solitary author; it emerges from communal and cultural memory. It is at once a sacred narrative involving divine beings, a form of history, and a tale infused with the fantastical. As myths are transmitted, received, and retold, their stories and meanings continually proliferate and transform. In this sense, they are “expressions of the ways in which humans have understood and responded to the world,” while also “containing the very foundations and culture of that understanding.”⁴ Consequently, reinterpretation and recreation across eras are inevitable.

Even within religion, to varying degrees, differences in perspective, attitude, and modes of interpretation are common subjects of discussion. When myths or doctrines are expressed through art, the scope of possible meanings expands even further. From prehistoric cave paintings to representational art, abstraction, and contemporary art, artworks function through signs and symbols. Thus, the viewer, the act of viewing, and the complex systems of signs and symbolic structures embedded within social meaning become crucial. For instance, a person unfamiliar with the doctrine of a particular religion cannot readily grasp the meaning of that religion’s sacred images. Fine art operates as a “social being” and as a form of “communication,” and while social conventions may impose constraints, they can also generate conditions for expanded diversity and change. For the same reason, artworks can be reinterpreted or endowed with new meanings long after the period in which they were created.⁵

Seen in this light, the liquefying, melting forms in Park Jung Hyuk’s paintings appear to underscore the insufficiency of singular, fixed meanings. Although he draws upon subjects with clear narratives and messages, he deliberately blends and dismantles them to construct visual contexts so layered and intricate that deciphering them can at times be difficult. This approach reinforces one of the essential qualities—and functions—of art: the endless generation of meaning and communication. It also asserts that any value judgment concerning these meanings cannot be definitive.

Park's Land 2, 2022, Oil on canvas, 162.2 x 112.1 cm ©Artist

Park's Land 25, 2023, Oil on canvas, 116.8 x 91 cm ©Artist

Of course, one must not overlook that “desire” is an indispensable theme in Park Jung Hyuk’s work, including the ‘Park’s Land’ series. As is widely recognized, humans are beings that desire. Beyond physical impulses, there exist psychic, emotional, and even metaphysical forms of desire. Desire itself is not inherently negative; it enables human life to be sustained and developed. Yet excess inevitably leads to unhappiness, making self-regulation essential. The figures portrayed in ‘Park’s Park’ and ‘Park’s Land’, however, unmistakably move toward the realm of excess.

‘Park’s Park’, in particular, visualizes a world in which consumption and possession have become primary mechanisms for fulfilling human desire, and everything—including faith and belief—is commodified. The characters in these paintings flounder in pleasure, unaware of what they themselves desire; they embody the modern condition of continual acquisition coupled with an unending sense of hunger. They also reveal the tragic reality of beings who have, in turn, become objects of desire. The sexually objectified bodies and unabashedly exposed nudity foreground taboo as a means to expose human duplicity, revealing a world in which even human existence is consumed under commercial and capitalist logics. The erotic charge that permeates these works recalls Sigmund Freud’s idea that sexual desire underlies all forms of desire, and that non-sexual desires can be understood as sublimated expressions of libido redirected toward different objects.⁶

Subsequently, the photographic clarity and hyper realistic rendering of earlier works transform in the ‘Park’s Memory’ series into simplified, thick gestures. The wavering images on the PET film foreground painting as both illusion and pigment laid upon a surface, while simultaneously evoking the diverse formal experiments characteristic of contemporary painting. The variable frames and silver film accentuate the materiality of the real world, dissolving one pictorial world while opening onto another—one that is autonomous yet porous, existing both as painting and as installation. Above all, the blurred forms trembling upon the film, together with the viewer’s reflection hovering over them, effectively mirror subjects and times unsettled by desire.

If ‘Park’s Park’ recontextualized and sharply exposed the secularization, standardization, and runaway acceleration of desire consumed within contemporary society, then ‘Park’s Land’ maintains its critical foundation while shifting toward a visualization of desire operating within the human interior—its nature and its impulses—mediated through myth and metamorphosis. Notably in ‘Park’s Land’, forms in which the boundaries between two or more bodies—two or more beings—appear liquefied and entangled recur throughout the series. These images invite multiple interpretations. Foremost, they conjure situations in which the physical or psychological boundaries between subjects become blurred: the act of eating, the condition of falling in love, or the moment of overwhelming affective fusion.

The artist depicts Erysichthon, who—having succumbed to arrogance and impiety by trespassing into the sacred grove of Ceres and cutting down a consecrated tree—was cursed with insatiable hunger and ultimately devoured his own body. Equally essential is Park’s Land 1 (2022), a transformation of Antonio Allegri’s Jupiter and Io (c. 1530).

Installation view of 《Rebellious possibility》 ©Leepoetique

Above all, ‘Park’s Land’ overflows with the artist’s desire to sublimate the incessant flood of images in contemporary life into artistic form, as well as his eagerness to present new work. Ours is an era governed by images—an era in which manipulation and distortion are more pervasive than ever. Images undergo ceaseless transformations. Eventually, the question of what the original might have been becomes irrelevant; the prototype dissolves as if melting away. Any boundary between original, copy, and edited version collapses. The artist withholds a clear judgment—neither affirming nor condemning this condition. He simply accepts it, recognizing it as an unavoidable dimension of the present.

Instead, he cites and assembles images within his practice in ways that intentionally destabilize the notion of originality. Neither the skies nor the seas in his paintings derive from a single source. Each form, drawn from disparate origins, is fragmented and reconnected through the artist’s actions. His use of visual imagery spanning multiple eras actively disrupts unity and coherence. Everything simply exists—here and now. And within this process, imagination and improvisation intervene.

Just as 『Metamorphoses』 persuasively renders minute details without allowing them to cohere into a single unified form,⁷ “the closer the work approached completion, the more the cited images transformed into unforeseen shapes, and the more dominant the images generated in the artist’s own mind became. As a result, the painting—an irregular mosaic, a puzzle with uncountable pieces—became a synthesis of images that simultaneously erase and retain hints of their origins, encompassing openness and closure of form and meaning, representation and expression, fields of color and abstraction, all at once—a totality of images that desires to possess everything.”⁸

Ultimately, Park Jung Hyuk’s works faithfully traverse the processes of receiving, observing, and producing images, yet the outcomes are hybrid forms in which the trace of originality becomes unrecognizable—while paradoxically realizing the most definitive original: the artwork itself. To break free from the prejudice surrounding painterly gesture, he chooses to “construct” painting through tools other than the hand or brush.⁹ In doing so, however, the aura and singularity of Park’s image-paintings are further intensified. Thus identity is repeatedly dismantled and reaffirmed.

Muscle memory drawing 20240623, 2024, Mixed media on photo collage, 21 x 21 cm ©Artist

This approach also applies to works in which memory takes center stage. Memory plays a significant role in shaping personal identity—it is inseparable from the life of the subject. As a visual producer and a participant in daily life, the artist experiences a vast array of information, some of which accumulates in memory and later informs his actions. Yet memory is endlessly erased and reproduced from the moment it is retained. It is not a definitive record with objective certainty, but is continuously transformed by the subject who remembers.

‘Muscle Memory Drawings’ (2017~), in which fragmented images of faces are presented in close-up and photos and drawings are interwoven, visualizes this particular quality of memory. Memory does not exist in isolation; through remembering, time itself becomes intertwined. Time that has passed is remembered, frozen, and then revived repeatedly. Moreover, since memory continues to operate in the future, just as the goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, knew the past, exists in the present, and is aware of all that is yet to come, memory encompasses past, present, and future.10

Meanwhile, the hybrids that appear in Park Jung Hyuk’s works can be read as symbols of the subject engaged in the continuous process of shedding past selves and constructing—or deconstructing—new identities within a given context. As previously noted, all beings in the world endlessly react and transform in ways akin to metamorphosis. A singular, stable subject or identity is impossible from the outset. This process can be arduous, painful, and chaotic. These hybrids, in part, evoke the notion of “becoming”.

Contrary to the common belief that desire arises from lacking something or having lost possession of something, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari describe desire as a primal force rooted in matter and the body, a free and productive energy that “produces the real,” functioning as “producers in and of reality.” Desire is fundamentally “a will to act”: to live, to speak, to think, to create. It determines “what one becomes” and the direction in which one pursues “becoming”.¹¹

Yet “becoming” is neither possession nor being. It designates an intermediate space “between one thing and another,” neither fixed nor assigned—a multiplicity, an “infinite lateral expansion” independent of origin. Park Jung Hyuk’s work, which endlessly differentiates and visualizes other forms of becoming, reflects an inquiry into his own existence and ultimately seeks to merge with the imperceptible becoming-with the world. It is neither metaphor nor identification; it is not imitation or assimilation, but entry into an unidentifiable domain.¹² Ultimately, “becoming” must be understood “not in terms of substantial meaning but as a verb,” as a process in which “series of potential points defining all objects or beings momentarily converge to produce a transformation.”¹³

Park's Land 23-1, 2024, Oil on canvas, 193.9 x 130.3 cm ©Artist

However, despite everything, the desire that Park Jung Hyuk pursues cannot completely escape—or evade—the system of identity and the gaze of power. The artist’s aspiration to secure his position within the art world circulates while still anchored to a point of centrality. The sources of inspiration accumulating within him, the deliberate or spontaneous creative processes triggered by logical reasoning and emotional impulses, the arrangement of color, form, and space, as well as experiments capable of dismantling preconceived notions while eliciting universal resonance—these elements, both internal and external, constitute the fundamental inquiry that drives his work.

This is simultaneously an attempt to step outside the structures that art has traditionally occupied and to enter them; whether he intends it or not, his works inevitably find a place within these frameworks. The self-contradiction is unavoidable. Park Jung Hyuk studies art history and tradition carefully, posing critical questions, responding to shifting ideas and aesthetics over time, and aiming toward fluidity rather than fixation. Yet, he simultaneously questions, endlessly, “Where does my work stand—or could stand—within art history, within the history of painting? What is the art-historical terrain of my own work?”¹⁴ Such reflections are perhaps inevitable for any conscientious artist. From this perspective, the hybrid forms in ‘Park’s Land’ do not depict endless acts of transgressive transformation or generation for the sake of resistance; rather, they portray situations that traverse singularity and multiplicity, oscillate between this and that, or occupy neither, thus giving rise to a sense of self-fragmentation.

Suddenly, the 「Epilogue」 of Ovid’s 『Metamorphoses』 comes to mind: “But I, the better part of me, shall endure / Carried up to those lofty stars, and my name shall not perish.”15 Naturally, “my heart urges me to sing the forms transformed into new bodies,”16 and the act of creation will continue. For now, we can only observe this ongoing process—a state of becoming, of transformation, in progress.

1) Calvino, Italo. “Ovid and the Vicinity of the Universe.” In Why Read the Classics, translated by Lee So-yeon, Minumsa, 2021, p. 53.

2) Kim, Ki-young. “The Meaning of Ovidian Transformation in the Epilogue of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (15.871–9).” Foreign Literature Studies, no. 51, 2013, p. 56.

3) Park, Jung Hyuk. “Artist’s Note,” 2023.

4) Hyun, Jung-sun. “Mythos and Logos, Myth and Reason.” German Language and Literature, vol. 173, 2025, p. 206.

Oh, Se-jung. “Violence and Culture, the Myth of the Scapegoat.” Humanities Studies, vol. 15, 2011, p. 74.

5) Risatti, Howard. A Theory of Craft, translated by Heo Bo-yoon, Mijinsa, 2013, pp. 152–153, 155–156, 160–161.

6) Lee, Jin-kyung. Nomadism 1, Humanist Publishing Group, 2016, p. 127.

7) Calvino, Italo. 2021, p. 45.

8) Lee, Moon-jung. “Metamorphosis, Seeking the Origin and the Process of Dismantling.” Public Art, no. 223, April 2025, p. 132.

9) Lee, Moon-jung and Park, Jung Hyuk. Artist Interview, February 17, 2025.

10) Jang, Young-ran. “Myth and Philosophy of Memory and Recollection.” Studies in Philosophy and Phenomenology, vol. 45, 2010, pp. 144–145.

11) Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Kim Jae-in, Minumsa, 2024, pp. 60–61.

Nam, Jung-ae. “A Study of the Motif of Metamorphosis Based on the Thought of Deleuze/Guattari.” Kafka Studies, vol. 30, 2013, pp. 61–62.

Lee, Jin-kyung. 2016, p. 129.

12) Kim, Jin-ok. “Becoming (Devenir) in Deleuze and Guattari and Virginia Woolf’s The Waves.” Phenomenon and Cognition, no. 128, 2016, pp. 126–127, 130.

13) Villani, Arnaud, and Robert Sasso (eds.). Dictionary of Deleuzian Concepts, translated by Shin Ji-young, Galmuri Publishing, 2013, p. 107.

14) Park, Jung Hyuk. Written Responses, February 25, 2025.

15) Ovid. Metamorphoses, translated by Cheon Byung-hee, Forest Publishing, 2023, p. 691.

16) Ovid. 2023, p. 24.